Object-Oriented Programming (OOP) is a cornerstone of modern software development. To truly grasp advanced principles like SOLID, it’s essential to start with a strong understanding of OOP fundamentals. This post will walk you through OOP concepts and then dive into the SOLID principles with simple examples to solidify your understanding.

Understanding Object-Oriented Programming (OOP)

Object-Oriented Programming revolves around the idea of representing real-world entities as objects. These objects encapsulate both data and behavior, making systems modular, reusable, and easier to maintain. Let’s break down the core principles of OOP.

1. Encapsulation: Protecting Data

Encapsulation involves bundling data (attributes) and behavior (methods) within a single class and restricting direct access to certain components.

Example

class BankAccount:

def __init__(self, owner, balance=0):

self.__balance = balance # Private attribute

def deposit(self, amount):

if amount > 0:

self.__balance += amount

def withdraw(self, amount):

if amount > 0 and amount <= self.__balance:

self.__balance -= amount

def get_balance(self):

return self.__balance

# Usage

account = BankAccount("Alice", 100)

account.deposit(50)

account.withdraw(30)

print(account.get_balance()) # Output: 120

2. Inheritance: Reusing Code

Inheritance allows classes to inherit attributes and methods from a parent class, promoting code reuse.

Example

class Vehicle:

def __init__(self, brand, speed):

self.brand = brand

self.speed = speed

def move(self):

print(f"The {self.brand} is moving at {self.speed} km/h")

class Car(Vehicle):

def honk(self):

print("Beep beep!")

# Usage

car = Car("Toyota", 100)

car.move() # Output: The Toyota is moving at 100 km/h

car.honk() # Output: Beep beep!

3. Polymorphism: Unified Interfaces

Polymorphism enables objects of different classes to be treated as objects of a common superclass.

Example

class Animal:

def make_sound(self):

pass

class Dog(Animal):

def make_sound(self):

print("Bark!")

class Cat(Animal):

def make_sound(self):

print("Meow!")

# Polymorphism in action

def animal_sound(animal):

animal.make_sound()

animal_sound(Dog()) # Output: Bark!

animal_sound(Cat()) # Output: Meow!

4. Abstraction: Hiding Complexity

Abstraction focuses on exposing essential details while hiding the underlying complexity.

Example

from abc import ABC, abstractmethod

class Shape(ABC):

@abstractmethod

def calculate_area(self):

pass

class Rectangle(Shape):

def __init__(self, width, height):

self.width = width

self.height = height

def calculate_area(self):

return self.width * self.height

# Usage

shape = Rectangle(5, 10)

print(shape.calculate_area()) # Output: 50

OOP Concepts in Real-World Scenarios

To help connect these principles, think of a software application like an e-commerce system:

- Encapsulation: Customer data (e.g., password) is protected and accessed only via secure methods.

- Inheritance: A “Product” class might serve as a base class for “Electronics” and “Clothing” subclasses.

- Polymorphism: A discount calculation can apply to various types of products in different ways but through a common interface.

- Abstraction: The user interacts with a “Place Order” button without needing to know the backend logic.

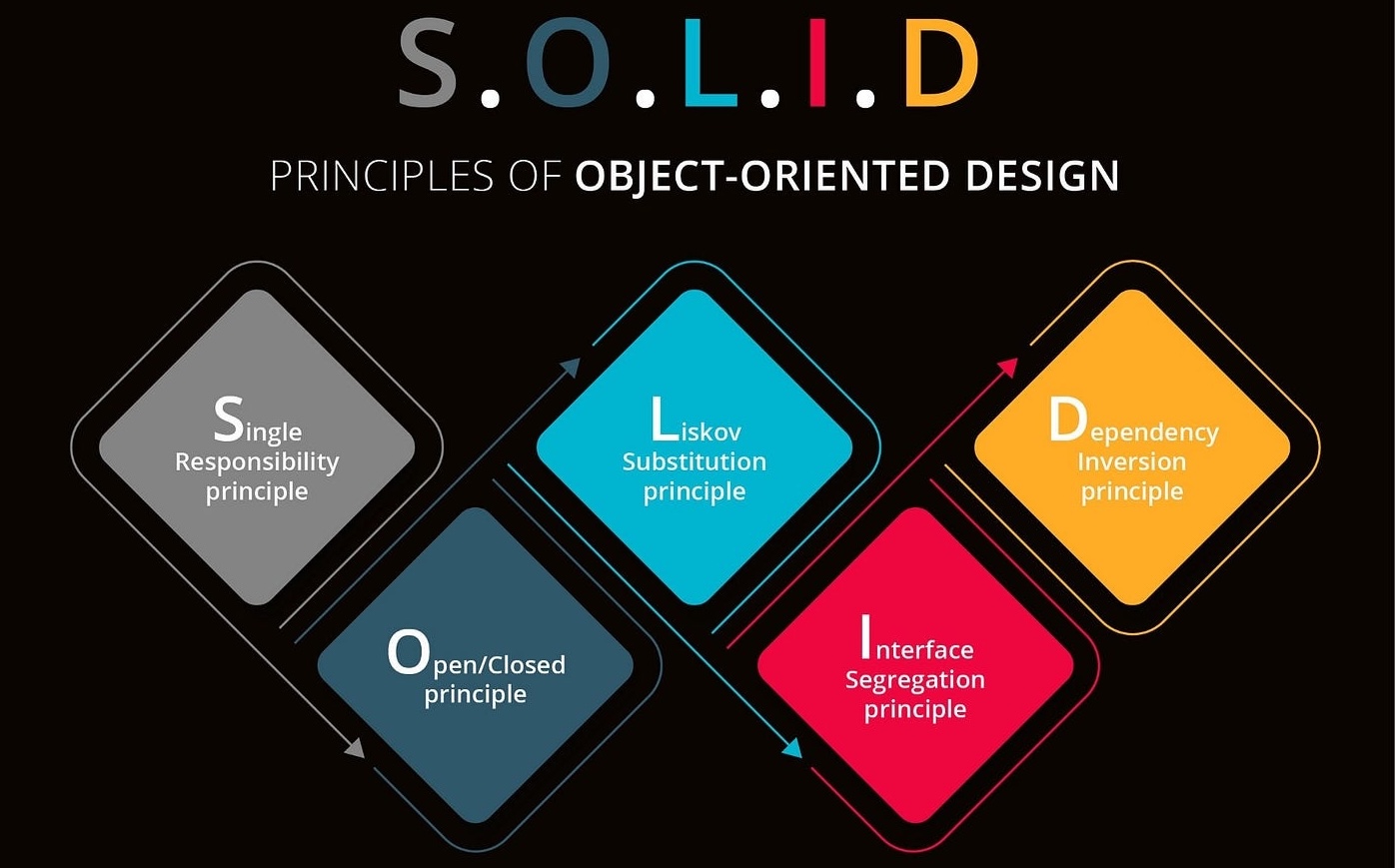

Introducing the SOLID Principles

The SOLID principles build on OOP concepts to ensure that your code is robust, maintainable, and scalable. Let’s explore each principle with simple examples.

1. Single Responsibility Principle (SRP)

A class should have only one reason to change, meaning it should perform only one responsibility.

Example

class Report:

def __init__(self, title, content):

self.title = title

self.content = content

class ReportFormatter:

def format_as_pdf(self, report):

# Logic to format as PDF

pass

class ReportSaver:

def save_to_file(self, report, filename):

# Logic to save the report

pass

Here, Report, ReportFormatter, and ReportSaver each have a single responsibility.

2. Open/Closed Principle (OCP)

Classes should be open for extension but closed for modification.

Example

Base Class:

from abc import ABC, abstractmethod

class PaymentProcessor(ABC):

@abstractmethod

def process_payment(self, amount):

pass

Subclasses:

class CreditCardProcessor(PaymentProcessor):

def process_payment(self, amount):

print(f"Processing credit card payment of {amount}")

class PayPalProcessor(PaymentProcessor):

def process_payment(self, amount):

print(f"Processing PayPal payment of {amount}")

Adding a new payment method doesn’t require modifying existing code—just create a new subclass.

3. Liskov Substitution Principle (LSP)

Subclasses should be replaceable for their base classes without altering the correctness of the program.

Example

Base Class:

from abc import ABC, abstractmethod

class PaymentProcessor(ABC):

@abstractmethod

def process_payment(self, amount):

pass

Subclasses:

class CreditCardProcessor(PaymentProcessor):

def __init__(self, amount, card_number, cvv):

self.amount = amount

self.card_number = card_number

self.cvv = cvv

def validate_payment(self):

print(f"Validating Credit Card: {self.card_number}")

if len(self.card_number) == 16 and len(str(self.cvv)) == 3:

print("Credit Card validated!")

return True

else:

print("Credit Card validation failed!")

return False

def process_payment(self):

if self.validate_payment():

print(f"Processing Credit Card payment of ${self.amount}.")

else:

print("Credit Card payment failed!")

class PayPalProcessor(PaymentProcessor):

def __init__(self, amount, email):

self.amount = amount

self.email = email

def validate_payment(self):

print(f"Validating PayPal email: {self.email}")

if "@" in self.email:

print("PayPal email validated!")

return True

else:

print("PayPal validation failed!")

return False

def process_payment(self):

if self.validate_payment():

print(f"Processing PayPal payment of ${self.amount}.")

else:

print("PayPal payment failed!")

Usage:

def process_transaction(payment):

payment.process_payment()

# Valid subclasses

credit_card = CreditCardProcessor(100, "1234567890123456", 123)

paypal = PayPalProcessor(200, "user@example.com")

process_transaction(credit_card)

process_transaction(paypal)

Violation: The InvalidPaymentProcessor bypasses payment validation, thus violating the LSP:

# Invalid subclass

class InvalidPaymentProcessor(PaymentProcessor):

def __init__(self, amount):

self.amount = amount

def process_payment(self):

# No validation is done; this can violate LSP if the system expects validation

print(f"Processing payment of ${self.amount} without validation.")

invalid_payment = InvalidPaymentProcessor(300)

process_transaction(invalid_payment) # Violates LSP

P.S. Although the base class doesn’t explicitly require validation, the other subclasses imply that process_payment should involve legitimate checks. By skipping them entirely, InvalidPaymentProcessor breaks that assumption—hence, it cannot replace other payment processors without altering the program’s correctness.

Why Bypass Validation Violates LSP Most parts of the system will assume that a valid payment is handled when process_payment completes. By not validating, InvalidPaymentProcessor contradicts this assumption. When substituted for a legitimate subclass, it changes the program’s expected behavior—thus violating LSP.

4. Interface Segregation Principle (ISP)

A class should not be forced to implement interfaces it does not use.

Example

class Workable:

def work(self):

pass

class Eatable:

def eat(self):

pass

class Human(Workable, Eatable):

def work(self):

print("Working")

def eat(self):

print("Eating")

class Robot(Workable):

def work(self):

print("Working")

Here, Robot doesn’t need the eat method, so we split the interfaces.

Common Pitfall A single, massive interface (often called a “God interface”) that forces all implementing classes to define methods they don’t need. Splitting into smaller interfaces prevents this bloat.

5. Dependency Inversion Principle (DIP)

High-level modules should not depend on low-level modules. Both should depend on abstractions.

Example

Base Class:

from abc import ABC, abstractmethod

class Developer(ABC):

@abstractmethod

def develop(self):

pass

Low-Level Classes:

class BackendDeveloper(Developer):

def develop(self):

print("Writing backend code")

class FrontendDeveloper(Developer):

def develop(self):

print("Writing frontend code")

High-Level Class:

class Project:

def __init__(self, developers):

self.developers = developers

def develop(self):

for dev in self.developers:

dev.develop()

Usage:

devs = [BackendDeveloper(), FrontendDeveloper()]

project = Project(devs)

project.develop()

Practical Angle In a large application (e.g., a microservices setup), you might have multiple specialized services. By introducing abstractions (like interfaces for each service), your higher-level modules can be coded against these interfaces. If one service changes (or if you add a new type of developer), you only need to create/modify the low-level module—not all the high-level modules.

Conclusion

Object-Oriented Programming and SOLID principles go hand in hand to create scalable, maintainable, and robust software. By understanding OOP concepts and applying SOLID principles, you can write code that adapts to change, reduces bugs, and promotes reuse.

Start practicing these principles in your projects today, and watch your codebase transform for the better!